Words and Their Shadows, the Snaking Line, and the Tiny Blades of Language: Cortney Lamar Charleston on His Poem "I'm Not a Racist"

Cortney Lamar Charleston

Cortney Lamar Charleston

Some write poetry with an eye towards beauty and their own experience, but it’s a different and very necessary kind of poet who arrives at the page with the intent to unsettle, to shake others from their sleep. From the instant I discovered him during my routine reading on the web, it was clear that Cortney Lamar Charleston is that other kind of writer – in his use of poetry both as art and as path to change, of everything from our relationships to the wider social fabric. In this time of violence against marginalized groups, it feels more important than ever to shed light on those artists who prod us awake to others’ pain, who keep us from rolling over and going back to sleep. I’m grateful to Cortney for the reminder, and for taking the time to do this interview – after just getting back from a retreat at Cave Canem, no less. – HLJ

===

I came across “I’m Not a Racist” in One Throne and instantly appreciated the truth-telling in it, this calling out of this country’s racial reality which is frankly a situation most people in my own experience are unlikely to discuss in “polite conversation.”

I’m really happy that you found the poem! Interestingly, I think the unlikelihood of race ever being part of polite conversation is the conceptual foundation of the entire poem. Because people try to avoid the topic completely, it leads to a lot of “mental gymnastics” aimed at skirting around the subject, but language has evolved in such a way that different words, when strung together, can mean the same thing. I can say that I’d rather avoid going to certain neighborhoods because they’re “sketchy” – or, I can say I don’t want to go to that neighborhood because it’s full of poor people or black people, or something along those lines. Either way, whether it’s explicit or implied, the meaning is the same because the word “sketchy” does not have a clean history. I pay less attention to someone’s exact words than to the shadow those words cast on me as the listener or reader.

===

I’M NOT A RACIST

I'm a realist: if I see a pack of hoods approaching, loitering,

acting a littering of public sidewalks, I simply

move to the other

side of the street, play it safe. I keep it on me at all times, for safety purposes.

In the event of open fire,

you'd be a hazard I told them when I, regrettably, couldn't

allow the lot of them into the party.

We're part of the same

political party, according to all the numbers I've seen.

When I shut the schools down, I was just

doing what must be done

to balance a city budget out of wack. When I put what

I found in his trunk on balance,

it was enough to tip the scale

towards a felony. I used to be a waiter, and they never

tipped very well in my experience.

While we were placing bets,

I noticed him tip his hand ever so slightly and there was

a ̶̶r̶a̶c̶e̶ face card in it. He didn't seem

like much of a bluffer, so I stood

my ground. On the grounds of merit – that's how I got

into Yale. I'm just not that into black

girls, personally. I mean, personally,

I don't SEE color. I'm so sorry, I really didn't see you there.

There they go, using that word again:

if they can say it, then why can't I?

I can't understand why everybody is so sensitive these days.

I admit, what I said sounded a little bit

insensitive, but believe me, I'm not

a racist. I'm a realist: if I see a pack of hoods approaching, loitering,

acting a littering of public sidewalks,

I simply move to the other side.

I keep it on me at all times, for purposes: in the event of a

hazard, open fire I told them, regrettably,

looking at the body splayed before me.

===

The speaker of this poem, the one who calls him- or herself a realist, is obviously blind to that shadow you mention, shut off to the gut-punch of that last line with its splayed body. I’ve since been digging up your other poems online (including “State of the Union” in Apogee Journal, and “Feeling Fucked Up” in the Poets Respond section of Rattle). They all seem to be tackling some of the biggest elephants in the room. And your poems remind me of what James Baldwin said about artists being here to disturb the peace, to rattle us out of our emotional safety and comfort – which is exactly what reading this poem did for me.

First and foremost, James Baldwin was a smart man and everybody should listen and take to heart to everything he has said or written. I’m definitely a disciple (or descendant maybe?) of his in regards to disturbing the peace. I’m glad you feel it is the work of rebellion that unsettles us out of our apathy and ignorance. That’s always the goal for me. There are so many people out in the world who don’t have that luxury, who have to move through the world with great concern for the respect of the sanctity of their body and the stability of their mind, all because what was built around them wasn’t built for them, if you get what I’m saying. Because I write with genuine concern for those people, my intentions are always to provoke, my purpose being to create room for empathy.

I resonate with what you said about a world being built around some people and not for them; we need only look as far as our history to see that. Could you tell us what inspired the poem? How did it first arrive for you?

To be completely honest, I’m not sure “where” the poem came from. Sure, I’m drawing from personal experiences as well as those that I know to have happened from others, but this particular poem is still kind of a mystery to me (or a miracle). Being a poet, I guess my natural tendency is to scrutinize words and try to squeeze the intent/meaning out of them. Race is a complex construct with a consequently complex language. It is the unspeakable that also must be spoken to in order for the world as we know it to function, to the benefit of some and the detriment of others, I must add. So we code the words. And me, I get my thrill from cracking them and making things plain.

I’m noticing how you re-spin some of these oft-spoken and frustratingly daft statements pertaining to race, such as “frankly, I don’t SEE color.” Or “there they go, using that word again.” How would you describe the transformation or revelation you’re aiming for with this kind of quoting of others’ comments pertaining to race?

As far as I know, they just say that’s calling people out. As far as revelation, I think the fact that I am using these common phrases forces readers into one of two camps who identify with one of these two statements: (1) I am harmed by this language, or (2) I use this language and do harm to others. Notice I didn’t say “to do harm”. Oftentimes, there is no inherently ill intention on the part of the speaker, but we have learned in our lives to kill one another slowly with these tiny blades of language. We have learned to behave in a way that injures others, and without looking at those words and actions, we really have no way of seeing them. In that sense, this poem is a trick mirror.

And then there’s that line that’s impossible to ignore, with its strikethrough: “I noticed him tip his hand ever so slightly and there was / a ̶̶r̶a̶c̶e̶ face card in it.” What’s happening here? Any technical or other lessons buried in this line?

I think the section you pulled touches on a disdain for blacks and other people of color speaking to the reality of their marginalization. The “race card” is not a tool that can be leveraged by people of color, it’s actually the other way around. It effectively silences their voices, limiting both their ability to protest and the effectiveness of whatever protests they stage. It also reminds us of the slipperiness of language and harkens back to the shadow of words I mentioned before. We can shuffle words around or refuse to speak certain things, but the shadow of what we believe is always present.

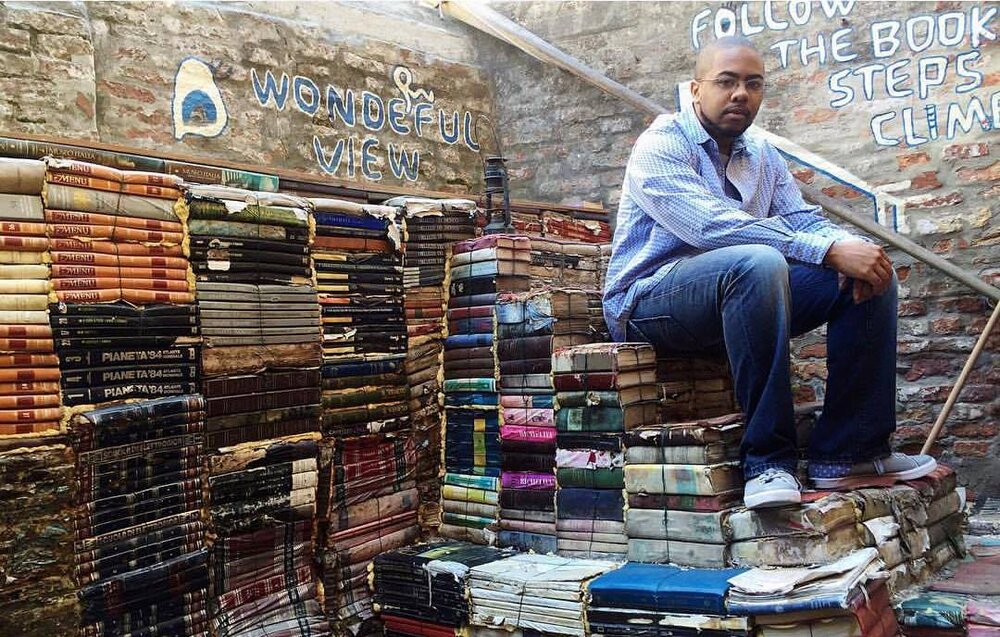

MLK and Malcolm meet: if you look closely, you can find Cortney in the middle.

MLK and Malcolm meet: if you look closely, you can find Cortney in the middle.

This rings so true; the importance of our attention to subtext. Now let’s go broader and talk a bit about the poem’s churning line breaks. How did you work those into the poem’s structure to enact its content?

When I think of this poem’s structure, I like to describe it as “snaking.” It’s a pun for sure, alluding to the fact that something is amiss, menacing but not easily detected. With that, I chose the specific breaks I did among these winding lines to play up tension or stress on certain words or phrases, places where the reader is supposed to glance in the mirror and hopefully see themselves.

If we were to see the words we write as an exercise of power, one could take the view (as I have) that all writers are propagandists whether they think of themselves that way or not. In submitting to journals, has it been more of a challenge placing those poems of yours that carry an explicit message around race (or social justice, or any other charged topic that might potentially unsettle a reader)?

I’ve been able to get my words out there thanks to the graciousness of a number of editors and publications, so on the surface, I should say no. But I still have that apprehension, because if I believe a poem is of publishable quality, then I have to always wonder (beyond considerations of how the poem is crafted) whether my content was off-putting to the venues where I submitted certain pieces that were turned down. There’s really no way of knowing. But I find this idea an interesting tangent to larger conversations about representation within the world of literature. The reason your question is a question, in my mind, is because editorship is still an overwhelmingly white and male exercise, and having that intersection of identities may create certain blind spots or come with certain biases, depending on one’s lived experience and political leanings. The more that begins to change (meaning the broad spectrum of gatekeepers begin to look more like the writers submitting), the more my anxiety and concern begins to dissipate.

That's a change I hope we can all advocate for. So there’s this other question about poetry as an act of witness … part of the risk in writing a poem of intense emotion is expressing what could wind up landing on the other side as a moral message. How have you navigated this challenge in this poem? In all the poems you write?

This is a tension I’m often trying to untangle in my writing. I certainly approach my writing with an idea of what is just, and wanting to push myself and the reader further in pursuit of that justness. At the same time, I don’t want to come off as preaching. I want the truth of a sermon, yes, but not at the expense of sounding as if I am somehow less fallible despite my strong sense of what is good, right or wrong. It’s a very difficult balance to find, but in my experience, having a clear concept to help channel my emotional energy in the process of writing helps to smooth out the tension. This poem itself is a great example of that. In a poem I rely on the language I hear around me to construct a new meaning, rather than devolve into passions that make it seem as if I’m screaming at the reader. I’m talking to them. They might even be talking to themselves.

Tell us a little about your poetry education. And is there any advice you'd offer to poets writing and practicing without the MFA?

My formal poetry education consists of any poetry units I’ve covered in my elementary, middle school and high school years and the wonderful instruction and guidance I’ve received as part of my Cave Canem fellowship. Beyond that, I also was part of a spoken word collective during my undergraduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania, but my academic concentrations there were in subjects other than English and Creative Writing. In that regard I’m probably more limited in formal education compared to most. But I also think that’s a good takeaway from poets who are writing without that structured curriculum and are not pursuing a MFA. I don’t believe programs can teach you how to write or find your voice; they offer an opportunity to study the work of others, learn the mechanics of poems (which you are capable of practicing intuitively or discern on your own) and give you the time and space to produce work and collaborate with other writers.

Any “homework” you’d like to assign our readers?

Yeah, I have an assignment for people… read Ocean Vuong’s debut collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds. Like yesterday.

Yes. An incredible poet.

Also, in regards to writing, I’d say to try and write a GHAZAL, simply because it’s my favorite form, one that’s easy to understand if you’re not used to working with forms, and one that invites your musicality to be on full and beautiful display.

Tell us a poem you love, and tell us why you love it.

Nicole Sealey’s “Object Permanence” which is available online via American Poetry Review. One thing that is absolutely clear to me after intensely writing for the past two years is that putting together a good love poem is incredibly difficult to do. It may be the most difficult poem to pull off. Sealey does it beautifully. The poem is precise and leaves no waste of words. It is built in the ordinary and the images are crisp. Finally, the last three lines are absolutely gorgeous, and mark transcendence within consciousness that speaks to what love really means. This is a poem, quite frankly, I aspire to in both the literal and figurative sense.

===

CORTNEY LAMAR CHARLESTON is a Cave Canem fellow, finalist for the 2015 Auburn Witness Poetry Prize and semi-finalist for the 2016 Discovery/Boston Review Poetry Prize. His poems have appeared, or are forthcoming, in Beloit Poetry Journal, Gulf Coast, Hayden's Ferry Review, The Iowa Review, The Journal, New England Review, Pleiades, River Styx, Spillway, TriQuarterly and elsewhere.